A brief look at past life expectancy

Year 1900

Year 1900

At the beginning of the 20th century, the average life expectancy in developed countries was forty-two. In developing countries, such as Brazil and Russia, the average was still below thirty. In India, deaths at birth were so common—and living conditions so poor—that average life expectancy was a mere twenty-three.

The concept of retirement only became widespread around the 1930’s, and paying heed to the future (both environmental and economic) of the planet was almost necessarily a vicarious practice.

Around 1930, the concept of a natural human lifespan was upturned. Suddenly, with deaths at birth and infectious diseases plummeting, conversations on climate change, long-term economic models—and even divorce—began to take place.

With the discovery of antibiotics, for the first time, humans were granted a pass into their future—along with the burden of choice, given that lifelong commitments now possessed wholly new meanings.

Whereas previously, nearly half of the world’s population could be expected to die of infectious diseases, humans almost overnight began to experience the full course of their “natural” lifespan—living up to 122 years of age and slowly dying, instead, of aging.

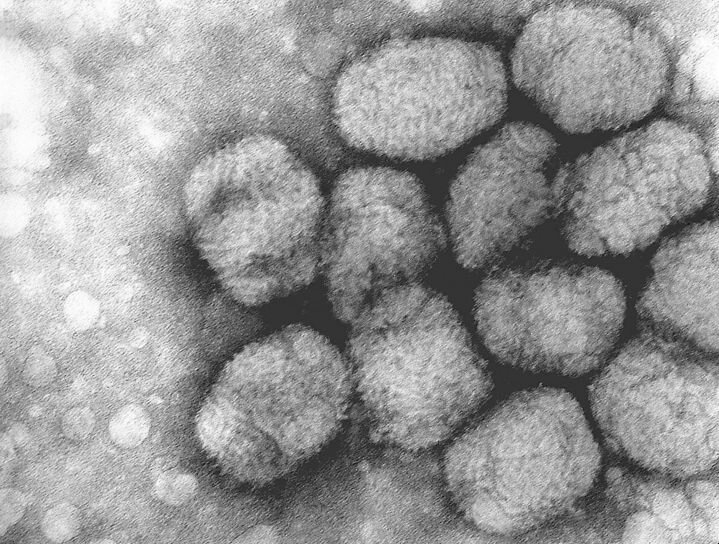

The vaccine against smallpox was developed in 1796, by Edward Jenner. In the 20th century, however, smallpox is estimated to have killed up to five hundred million people—five times the number of deaths from the two World Wars combined.

Up until the 1900’s, smallpox was seen as a natural part of life. The thought that a millennia-old disease could be done away with seemed idealistic. Until, suddenly, it didn’t.

Around 1950, the World Health Organization went on a mission to distribute smallpox vaccination worldwide. Late in the 20th century, this was a cultural—more than a scientific—revolution.

Despite the development of the first vaccine for smallpox in 1796, it took nearly two centuries—and not far from a billion deaths—for the disease to be eradicated, in 1979.

In 2019, the three leading causes of death worldwide—cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancers, respectively—are the diseases of aging. According to the National Cancer Institute, only 3.7% of all cancer patients are aged 34 or younger.

This suggests that today’s leading causes of death—including COVID-19, with a mortality rate of 0.2% for patients under forty—may be more profitably observed as effects of aging. Individually, the treatment of any single disease of aging would fail to significantly augment human health or life span. Combined, however, they kill over 100,000 people daily.

were paid to 26.9 million retired Americans in 2016.

is the amount of US taxpayer dollars spent in 2021 on the care for those with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias (which affect people aged forty or older 99% of the time).

The Epic of Gilgamesh is said to be the earliest surviving work of literature. In it, a young and vain king goes on an ill-starred quest for immortality, only to learn that his attempt had been in vain.

In the 21st century, even if the nobility linked to the acceptance of death is bypassed, the pervasive sentiment on the possibility of life-extension remains:

The answer lies in the very recent wedding of healthcare to information technology. In “Longevity: The Greatest Investment Opportunity of All Time,” Jim Mellon explains how our current quest differs from previous attempts at chasing not just longer, but healthier lives.

Without healthy, active populations, generating new ideas and critiquing old ones, all of humanity’s risks are exacerbated. If the existential risk posed by artificial intelligence is a problem, the lack of persons ideating on how to best align AI magnifies it. If nuclear risk is a catastrophic or existential threat, the lack of talent thinking up solutions to this crisis increases the likelihood of our demise. If resource scarcity is the result of poorly aligned technological advancement, a dearth of people working to solve our century’s most pressing issues exacerbates the misdistribution of material wealth.

By 2050, the global population is expected to reach ten billion. But the graph above demonstrates that the few countries still undergoing population growth in 2022 will soon see their rates plummet. Absent high immigration rates, several countries in the world would have already seen their birth rates dangerously shrink—as is the case for most European countries; and for Japan, as it is set to lose some 20 million people by 2050.

Without waves of young immigrants in the US, some forty percent of the American population would consist of people aged sixty and over. Given the shortness of our current health-span, this would be no less than an economic fiasco.

Governments are burdened not by an excessive number of living people, but by unprecedentedly long-lived populations whose health-span hasn’t yet caught up to an increase in lifespan. This means that a larger number of healthy, long-lived individuals is likelier to mend financial structures than to burden them.

This number consists mostly of retirees, children, and college/graduate students: people who are neither employed, nor unemployed. In developed nations, inactive populations consist primarily of people aged fifty and older: a trend quickly expanding to the developing world.

Ethical concerns as it regards overpopulation, then, are more closely linked to the health-span of a given population than to its lifespan.

If an effective treatment for the fundamental processes of aging were found today, trillions of US dollars could be allocated towards technologies designed to circumvent the misdistribution of resources; or toward the democratization of (then less-burdened) national health services.

If, however, aging is not treated, but lifespan continues to increase—as it has—ethical problems are sure to arise. In 1900, when the majority of deaths were caused by infectious diseases, deaths were, as a rule, quick and inexpensive. Today, not seldom, people live for a total of fifty years as a non-contributing part of the population (25 as young adults + 25 as older adults).

Credit: Holden Karnofsky.

In The Most Important Century, Holden Karnofsky illustrates how the creation of more minds would enable accelerated economic growth. Karnofsky also posits that the development of “digital minds” would incite even more growth, enabling us, for the first time in history, to conduce rigorous experiments in the social sciences (e.g., comparing how different personal choices may produce better or worse outputs for “the good life”); and to capitalize on rapid results, from research which would be deemed unethical if carried on in biological humans.

In the Effective Altruism community, AI development and, more importantly, alignment, is rightly seen as a priority cause area. Yet, I suggest, duplicator-like technologies (even absent the benefits conferred by digital copies) remain worthy of pursuit, and are likely to become the greatest natural resource of our times. Because there’s no guarantee that superintelligence will arise within the coming decade(s), the development of age-reversing technologies (which could effectively duplicate the healthy lifespan of every living human) is still a worthwhile mission.

Yes, in the coming decades, Artificial Intelligence will increasingly inform the healthcare industry—and at some point, I’m confident, the two will converge. And yes, the existential risk posed by misaligned AI ought to receive hefty funding. But just as investing in carbon-reversing technologies continues to make sense, so too, does the investment in and development of age-reversing technologies.

Because aging is the primary cause of the majority of deaths today, this eery, and somewhat impractical question, may well be replaced by: “Do you want to get Alzheimer's today? Or a type of cancer; diabetes; or a stroke?”

I believe that no single suicidal person—if they do not also happen to be a masochist—would be quick to answer yes to any of these questions. There are quicker, and certainly less expensive ways to die.

Whether or not one should like to live forever, one will not, in this first half of our century, need answer. Instead, the questions at hand may more profitably be:

As a species, we are defined by our ability to overcome, override and overwrite nature. It is naive to assume that we, in our mammalian form, constitute the final product of evolution. Life—and especially human life—is premised on the condition of change, whereas death rests on sameness. Life is transient, fleeting, and full of breaks. Death, on the other hand, is forever.

Life is the possibility of new events, plural. Death, and in particular death as it exists in the 21st century—by the diseases of aging—is unprecedentedly costly, cruel, and harmful to human civilizations.

Do the old need to perish for the young to thrive, or does progress result from something other than funerals?

Change, I think, occurs when living – not dead – people spur it. Progress isn’t a mystical, dialectical or predetermined process, which wondrously unfolds as soon as burials take place. Progress is the result of the hard work and actions of innovative, living thinkers — like Vitalik Buterin, who co-founded the decentralized blockchain Ethereum at 23 years old, and like Henry Ford, who created the Model T (the world’s first affordable car) at 45.

Progress happens not one funeral, but one healthy, living human at a time. It is not up to the allegorical workings of death, but to each living human to advance our ethics, our politics and our technologies. To reject the development of life-extending therapies on the basis that ill-meaning actors or regimes may live on is as rational as it is to oppose treatments for Alzheimer’s, lest we end up with non-demented autocrats.

__________________________________